The culture of Japan has evolved greatly over millennia, from the country's prehistoric Jōmon period to its contemporary hybrid culture, which combines influences from Asia, Europeand North America. The inhabitants of Japan experienced a long period of relative isolation from the outside world during the Tokugawa shogunate until the arrival of "The Black Ships" and the Meiji period.

Japanese language

The Japanese language is spoken mainly in Japan but also in some Japanese emigrant communities around the world. It is an agglutinative language and the sound inventory of Japanese is relatively small but has a lexically distinct pitch-accent system. Early Japanese is known largely on the basis of its state in the 8th century, when the three major works of Old Japanese were compiled. The earliest attestation of the Japanese language is in a Chinese document from 252 A.D.

Japanese is written with a combination of three scripts: hiragana, derived from the Chinese cursive script, katakana, derived as a shorthand from Chinese characters, and kanji, imported from China. The Latin alphabet, rōmaji, is also often used in modern Japanese, especially for company names and logos, advertising, and when inputting Japanese into a computer. The Hindu-Arabic numerals are generally used for numbers, but traditional Sino-Japanese numerals are also common.

Literature

Visual artsPainting

Painting has been an art in Japan for a very long time: the brush is a traditional writing tool, and the extension of that to its use as an artist's tool was probably natural. Chinese papermaking was introduced to Japan around the 7th century by Damjing and several monks ofGoguryeo,[1] later washi was developed from it. Native Japanese painting techniques are still in use today, as well as techniques adopted fromcontinental Asia and from the West.

Calligraphy

The flowing, brush-drawn Japanese language lends itself to complicated calligraphy. Calligraphic art is often too esoteric for Western audiences and therefore general exposure is very limited. However in East Asian countries, the rendering of text itself is seen as a traditional art form as well as a means of conveying written information. The written work can consist of phrases, poems, stories, or even single characters. The style and format of the writing can mimic the subject matter, even to the point of texture and stroke speed. In some cases it can take over one hundred attempts to produce the desired effect of a single character but the process of creating the work is considered as much an art as the end product itself.

This art form is known as ‘Shodo’ (書道) which literally means ‘the way of writing or calligraphy’ or more commonly known as ‘Shuji’ (習字) ‘learning how to write characters’.

Commonly confused with Calligraphy is the art form known as ‘Sumi-e’ (墨絵) literally means ‘ink painting’ which is the art of painting a scene or object.

Sculpture

Traditional Japanese sculptures mainly consisted of Buddhist images, such as Tathagata, Bodhisattva and Myō-ō. The oldest sculpture in Japan is a wooden statue of Amitābha at the Zenkō-ji temple. In the Nara period, Buddhist statues were made by the national government to boost its prestige. These examples are seen in present-day Nara and Kyoto, most notably a colossal bronze statue of the Buddha Vairocanain the Tōdai-ji temple.

Wood has traditionally been used as the chief material in Japan, along with the traditional Japanese architectures. Statues are often lacquered,gilded, or brightly painted, although there are little traces on the surfaces. Bronze and other metals are also used. Other materials, such asstone and pottery, have had extremely important roles in the plebeian beliefs.

Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e, literally "pictures of the floating world", is a genre of woodblock prints that exemplifies the characteristics of pre-Meiji Japanese art. Because these prints could be mass-produced, they were available to a wide cross-section of the Japanese populace — those not wealthy enough to afford original paintings — during their heyday, from the 17th to 20th century.

Ikebana

Ikebana (生花) is the Japanese art of flower arrangement. It has gained widespread international fame for its focus on harmony, color use, rhythm, and elegantly simple design. It is an art centered greatly on expressing the seasons, and is meant to act as a symbol to something greater than the flower itself. Traditionally, when third party marriages were more prominent and practiced in Japan, many Japanese women entering into a marriage learned to take up the art of Ikebana to be a more appealing and well-rounded lady. Today Ikebana is widely practiced in Japan, as well as around the world.

Performing arts

The four traditional theatres from Japan are noh, kyogen, kabuki and bunraku. Noh had its origins in the union of the sarugaku with music and dance made by Kanami and Zeami Motokiyo.[2] Among the characteristic aspects of it are the masks, costumes and the stylized gestures, sometimes accompanied by a fan that can represent other objects. The nohprograms are presented in alternation with the ones of kyogen, traditionally in number of five, but currently in groups of three. The kyogen, of humorous character, had older origin, in 8th century entertainment brought from China, developing itself in sarugaku. In kyogen masks are rarely used and even if the plays can be associated with the ones of noh, currently many are not. Kabuki appears in the beginning of the Edo period from the representations and dances of Izumo no Okuni in Kyoto. Due to prostitution of actresses of kabuki the participation of women in the plays was forbidden by the government in 1629 and the feminine characters had passed to be represented only by men (onnagata). Recent attempts to reintroduce actresses in kabuki had not been well accepted. Another characteristic of kabuki is the use of makeup for the actors in historical plays (kumadori). Japanese puppet theater bunraku developed in the same period that kabuki in a competition and contribution relation involving actors and authors. The origin of bunraku however is older, lies back in theHeian period. In 1914 appeared the Takarazuka Revue a company solely composed by women who introduced the revue in Japan.

Architecture

Japanese architecture has as long a history as any other aspect of Japanese culture. Originally heavily influenced by Chinese architecture, it also develops many differences and aspects which are indigenous to Japan. Examples of traditional architecture are seen at Temples, Shinto shrines and castles in Kyoto, and Nara. Some of these buildings are constructed with traditional gardens, which are influenced from Zen ideas.

Some modern architects, such as Yoshio Taniguchi and Tadao Ando are known for their amalgamation of Japanese traditional and Western architectural influences.

Gardens

Garden architecture is as important as building architecture and very much influenced by the same historical and religious background. Although today, ink monochrome painting still is the art form most closely associated with Zen Buddhism. A primary design principle of a garden is the creation of a landscape based on, or at least greatly influenced by, the three-dimensional monochrome ink (sumi) landscape painting, sumi-e or suibokuga.

In Japan, the garden has the status of artwork.

Traditional clothing

Traditional Japanese clothing distinguishes Japan from all other countries around the world. The Japanese word kimono means "something one wears" and they are the traditional garments of Japan. Originally, the word kimono was used for all types of clothing, but eventually, it came to refer specifically to the full-length garment also known as the naga-gi, meaning "long-wear", that is still worn today on special occasions by women, men, and children. Kimono in this meaning plus all other items of traditional Japanese clothing is known collectively as wafuku which means "Japanese clothes" as opposed to yofuku (Western-style clothing). Kimonos come in a variety of colours, styles, and sizes. Men mainly wear darker or more muted colours, while women tend to wear brighter colors and pastels, and, especially for younger women, often with complicated abstract or floral patterns.

The kimono of a woman who is married (Tomesode) differs from the kimono of a woman who is not married (Furisode). The Tomesode sets itself apart because the patterns do not go above the waistline. The Furisode can be recognized by its extremely long sleeves spanning anywhere from 39 to 42 inches, it is also the most formal kimono an unwed woman wears. The Furisode advertises that a woman is not only of age but also single.

The style of kimono also changes with the season, in spring kimonos are vibrantly colored with springtime flowers embroidered on them. In the fall, kimono colors are not as bright, with fall patterns. Flannel kimonos are ideal for winter, they are a heavier material to help keep you warm.

One of the more elegant kimonos is the uchikake, a long silk overgarment worn by the bride in a wedding ceremony. The uchikake is commonly embellished with birds or flowers using silver and gold thread.

Kimonos do not come in specific sizes as most western dresses do. The sizes are only approximate, and a special technique is used to fit the dress appropriately.

The obi is a very important part of the kimono. Obi is a decorative sash that is worn by Japanese men and women, although it can be worn with many different traditional outfits, it is most commonly worn with the kimono. Most women wear a very large elaborate obi, while men typically don a more thin and conservative obi.

Most Japanese men only wear the kimono at home or in a very laid back environment, however it is acceptable for a man to wear the kimono when he is entertaining guests in his home. For a more formal event a Japanese man might wear the haori and hakama, a half coat and divided skirt. The hakama is tied at the waist, over the kimono and ends near the ankle. Hakama were initially intended for men only, but today it is acceptable for women to wear them as well. Hakama can be worn with types of kimono, excluding the summer version,yukata. The lighter and simpler casual-wear version of kimono often worn in summer or at home is called yukata.

Formal kimonos are typically worn in several layers, with number of layers, visibility of layers, sleeve length, and choice of pattern dictated by social status, season, and the occasion for which the kimono is worn. Because of the mass availability, most Japanese people wear western style clothing in their everyday life, and kimonos are mostly worn for festivals, and special events. As a result, most young women in Japan are not able to put the kimono on themselves. Many older women offer classes to teach these young women how to don the traditional clothing.

Happi is another type of traditional clothing, but it is not famous worldwide like the kimono. A happi (or happy coat) is a straight sleeved coat that is typically imprinted with the family crest, and was a common coat for firefighters to wear.

Japan also has very distinct footwear. Tabi, an ankle high sock, is often worn with the kimono. Tabi are designed to be worn with geta a type of thonged footwear. Geta are sandals mounted on wooden blocks held to the foot by a piece of fabric that slides between the toes. Geta are worn both by men and women with the kimono or yukata.

Kimono

The kimono (着物) is a Japanese traditional garment worn by women, men and children. The word "kimono", which literally means a "thing to wear" (ki "wear" and mono "thing"), has come to denote these full-length robes. The standard plural of the word kimono in English is kimonos,but the unmarked Japanese plural kimono is also sometimes used.

Kimono are T-shaped, straight-lined robes worn so that the hem falls to the ankle, with attached collars and long, wide sleeves. Kimono are wrapped around the body, always with the left side over the right (except when dressing the dead for burial), and secured by a sash called anobi, which is tied at the back. Kimono are generally worn with traditional footwear (especially zōri or geta) and split-toe socks (tabi).

Today, kimono are most often worn by women, and on special occasions. Traditionally, unmarried women wore a style of kimono calledfurisode, with almost floor-length sleeves, on special occasions. A few older women and even fewer men still wear the kimono on a daily basis. Men wear the kimono most often at weddings, tea ceremonies, and other very special or very formal occasions. Professional sumo wrestlers are often seen in the kimono because they are required to wear traditional Japanese dress whenever appearing in public.

As the kimono has another name, gofuku (呉服, literally "clothes of Wu (吳)"), the earliest kimonos were heavily influenced by traditional Han Chinese clothing, known today as hanfu (漢服, kanfuku in Japanese), through Japanese embassies to China which resulted in extensive Chinese culture adoptions by Japan, as early as the 5th century CE. It was during the 8th century, however, that Chinese fashions came into style among the Japanese, and the overlapping collar became particularly a women's fashion. During Japan's Heian period (794–1192 CE), the kimono became increaslingly stylized, though one still wore a half-apron, called a mo, over it. During the Muromachi age(1392–1573 CE), the Kosode, a single kimono formerly considered underwear, began to be worn without the hakama (trousers, divided skirt) over it, and thus began to be held closed by an obi "belt". During the Edo period (1603–1867 CE), the sleeves began to grow in length, especially among unmarried women, and the Obi became wider, with various styles of tying coming into fashion. Since then, the basic shape of both the men’s and women’s kimono has remained essentially unchanged. Kimonos made with exceptional skill from fine materials have been regarded as great works of art.

History

The formal kimono was replaced by the more convenient Western clothes and Yukata as everyday wear. After an edict by Emperor Meiji, police, railroad men and teachers moved to Western clothes. The Western clothes became the army and school uniform for boys. After the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, kimono wearers often became victims of robbery because they could not run very fast due to the restricting nature of the kimono on the body and geta slippers. The Tokyo Women's & Children's Wear Manufacturers' Association (東京婦人子供服組合) promoted Western clothes. Between 1920 and 1930 the sailor outfit replaced the undivided hakama in school uniforms for girls. The 1932 fire atShirokiya's Nihonbashi store is said to have been the catalyst for the decline in kimonos as everyday wear. Kimono-clad Japanese women did not wear panties and several women refused to jump into safety nets because they were ashamed of being seen from below. (It is, however, suggested, that this is an urban myth.) The national uniform, Kokumin-fuku(国民服), a type of Western clothes, was mandated for males in 1940. Today most people wear Western clothes and wear the breezier and more comfortable yukata for special occasions.

Textiles and manufacture

Kimonos for men are available in various sizes and should fall approximately to the ankle without tucking. A woman's kimono has additional length to allow for the ohashori, the tuck that can be seen under the obi, which is used to adjust the kimono to the individual wearer. An ideally tailored kimono has sleeves that fall to the wrist when the arms are lowered.

Kimonos are traditionally made from a single bolt of fabric called a tan. Tan come in standard dimensions—about 14 inches wide and 12½ yards long—and the entire bolt is used to make one kimono. The finished kimono consists of four main strips of fabric—two panels covering the body and two panels forming the sleeves—with additional smaller strips forming the narrow front panels and collar. Historically, kimonos were often taken apart for washing as separate panels and resewn by hand. Because the entire bolt remains in the finished garment without cutting, the kimono can be retailored easily to fit a different person.

The maximum width of the sleeve is dictated by the width of the fabric. The distance from the center of the spine to the end of the sleeve could not exceed twice the width of the fabric. Traditional kimono fabric was typically no more than 36 centimeters (14 inches) wide. Thus the distance from spine to wrist could not exceed a maximum of roughly 68 centimeters (27 inches). Modern kimono fabric is woven as wide as 42 centimeters (17 inches) to accommodate modern Japanese body sizes. Very tall or heavy people, such as sumo wrestlers, must have kimonos custom-made by either joining multiple bolts, weaving custom-width fabric, or using non-standard size fabric.

Traditionally, kimonos are sewn by hand, but even machine-made kimonos require substantial hand-stitching. Kimono fabrics are also frequently hand made and hand decorated. Various techniques such as yūzen dye resist are used for applying decoration and patterns to the base cloth. Repeating patterns that cover a large area of a kimono are traditionally done with the yūzen resist technique and a stencil. Over time there have been many variations in color, fabric and style, as well as accessories such as the obi.

The kimono and obi are traditionally made of silk, silk brocade, silk crepes (such as chirimen) and satin weaves (such as rinzu). Modern kimonos are also widely available in less-expensive easy-care fabrics such as rayon, cotton sateen, cotton, polyester and other synthetic fibers. Silk is still considered the ideal fabric.

Customarily, woven patterns and dyed repeat patterns are considered informal. Formal kimonos have free-style designs dyed over the whole surface or along the hem. During the Heian period, kimonos were worn with up to a dozen or more colorful contrasting layers, with each combination of colors being a named pattern. Today, the kimono is normally worn with a single layer on top of one or more undergarments. The pattern of the kimono can also determine in which season it should be worn. For example, a pattern with butterflies or cherry blossoms would be worn in spring. Watery designs are common during the summer. A popular autumn motif is the russet leaf of the Japanese maple; for winter, designs may include bamboo, pine trees and plum blossoms.

A popular form of textile art in Japan is shibori (intricate tie dye), found on some of the more expensive kimonos and haori kimono jackets. Patterns are created by minutely binding the fabric and masking off areas, then dying it, usually done by hand. When the bindings are removed, an undyed pattern is revealed. Shibori work can be further enhanced with yuzen (hand applied) drawing or painting with textile dyes or with embroidery; it is then known as tsujigahana. Shibori textiles are very time consuming to produce and require great skill, so the textiles and garments created from them are very expensive and highly prized.

Old kimonos are often recycled in various ways: altered to make haori, hiyoku, or kimonos for children, used to patch similar kimono, used for making handbags and similar kimono accessories, and used to make covers, bags or cases for various implements, especially for sweet-picks used in tea ceremonies. Damaged kimonos can be disassembled and resewn to hide the soiled areas, and those with damage below the waistline can be worn under a hakama. Historically, skilled craftsmen laboriously picked the silk thread from old kimono and rewove it into a new textile in the width of a heko obi for men's kimono, using a recycling weaving method called saki-ori.

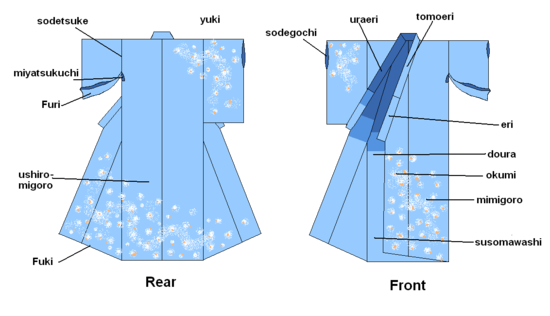

Parts of a kimono

Various terms refer to parts of a kimono, as listed below.

- Dōura (胴裏): upper lining on a woman's kimono.

- Eri (衿): collar.

- Fuki: hem guard.

- Furi: sleeve below the armhole.

- Maemigoro (前身頃): front main panel, excluding sleeves. The covering portion of the other side of the back, maemigoro is divided into "right maemigoro" and "left maemigoro".

- Miyatsukuchi: opening under the sleeve.

- Okumi (衽): front inside panel situated on the front edge of the left and right, excluding the sleeve of a kimono. Until the collar, down to the bottom of the dress goes, up and down part of the strip of cloth. Have sewn the front body. It is also called "袵".

- Sode (袖): sleeve

- Sodeguchi (袖口): sleeve opening.

- Sodetsuke (袖付): kimono armhole.

- Susomawashi (裾回し): lower lining.

- Tamoto (袂): sleeve pouch.

- Tomoeri (共衿): over-collar (collar protector).

- Uraeri (裏襟): inner collar.

- Ushiromigoro (後身頃): back main panel, excluding sleeves, covering the back portion. They are basically sewn back-centered and consist of "right ushiromigoro" and "left ushiromigoro", but for wool fabric, the ushiromigoro consists of one piece.

Cost

A woman's kimono may easily exceed US$10,000; a complete kimono outfit, with kimono, undergarments, obi, ties, socks, sandals, and accessories, can exceed US$20,000. A single obi may cost several thousand dollars. However, most kimonos owned by kimono hobbyists or by practitioners of traditional arts are far less expensive. Enterprising people make their own kimono and undergarments by following a standard pattern, or by recycling older kimonos. Cheaper and machine-made fabrics can substitute for the traditional hand-dyed silk. There is also a thriving business in Japan for second-hand kimonos, which can cost as little as ¥500 (about $5). Women's obis, however, mostly remain an expensive item. Although simple patterned or plain colored ones can cost as little as ¥1,500 (about $15), even a used obi can cost hundreds of dollars, and experienced craftsmanship is required to make them. Men's obis, even those made from silk, tend to be much less expensive, because they are narrower, shorter and less decorative than those worn by women.

Styles

Kimonos range from extremely formal to casual. The level of formality of women's kimono is determined mostly by the pattern of the fabric, and color. Young women's kimonos have longer sleeves, signifying that they are not married, and tend to be more elaborate than similarly formal older women's kimono. Men's kimonos are usually one basic shape and are mainly worn in subdued colors. Formality is also determined by the type and color of accessories, the fabric, and the number or absence of kamon(family crests), with five crests signifying extreme formality.n Silk is the most desirable, and most formal, fabric. Kimonos made of fabrics such as cotton and polyester generally reflect a more casual style. It is said that the reason of these long sleeves is when confessed by man, in case of replying "Yes," she waves sleeves back and forth, but as for "no" left to right.

Women's kimonos

Many modern Japanese women lack the skill to put on a kimono unaided: the typical woman's kimono outfit consists of twelve or more separate pieces that are worn, matched, and secured in prescribed ways, and the assistance of licensed professional kimono dressers may be required. Called upon mostly for special occasions, kimono dressers both work out of hair salons and make house calls.

Choosing an appropriate type of kimono requires knowledge of the garment's symbolism and subtle social messages, reflecting the woman's age, marital status, and the level of formality of the occasion rangers between all different placers in japan.

Furisode

- (振袖): furisode literally translates as swinging sleeves—the sleeves of furisode average between 39 and 42 inches (1,100 mm) in length.Furisode are the most formal kimono for unmarried women, with colorful patterns that cover the entire garment. They are usually worn at coming-of-age ceremonies (seijin shiki) and by unmarried female relatives of the bride at weddings and wedding receptions.

Hōmongi

- (訪問着): literally translates as visiting wear. Characterized by patterns that flow over the shoulders, seams and sleeves, hōmongi rank slightly higher than their close relative, the tsukesage. Hōmongi may be worn by both married and unmarried women; often friends of the bride will wear hōmongi at weddings (except relatives) and receptions. They may also be worn to formal parties.

- Pongee Hōmongi were made to promote kimono after WW2. Pongee is used for casual clothes, so they are not for formal occasions no matter how expensive they are.

Iromuji

- (色無地): single-colored kimono that may be worn by married and unmarried women. They are mainly worn to tea ceremonies. The dyed silk may be figured (rinzu, similar to jacquard), but has no differently colored patterns.

Komon

- (小紋): "fine pattern". Kimono with a small, repeated pattern throughout the garment. This style is more casual and may be worn around town, or dressed up with a formal obi for a restaurant. Both married and unmarried women may wear komon.

- Edo komon

- (江戸小紋): is a type of komon characterized by tiny dots arranged in dense patterns that form larger designs. The Edo komon dyeing technique originated with the samurai class during the Edo period. A kimono with this type of pattern is of the same formality as an iromuji, and when decorated with kamon, may be worn as visiting wear (equivalent to a tsukesage or hōmongi).

Mofuku

- Mofuku is formal mourning dress for men or women. Both men and women wear kimono of plain black silk with five kamon over white undergarments and white tabi. For women, theobi and all accessories are also black. Men wear a subdued obi and black and white or black and gray striped hakama with black or white zori.

- The completely black mourning ensemble is usually reserved for family and others who are close to the deceased.

Tomesode

- Irotomesode

- (色留袖): single-color kimono, patterned only below the waistline. Irotomesode are slightly less formal than kurotomesode, and are worn by married women, usually close relatives of the bride and groom at weddings. An irotomesode may have three or five kamon.

- Kurotomesode

- (黒留袖): a black kimono patterned only below the waistline, kurotomesode are the most formal kimono for married women. They are often worn by the mothers of the bride and groom at weddings. Kurotomesode usually have five kamon printed on the sleeves, chest and back of the kimono.

Tsukesage

- (付け下げ): has more modest patterns that cover a smaller area—mainly below the waist—than the more formal hōmongi. They may also be worn by married women.The differences from homongi is the size of the pattern, seam connection, and not same clothes at inside and outside at "hakke" As demitoilet, not used in important occasion, but light patterned homongi is more highly rated than classic patterned tsukesage. General tsukesage is often used for party, not ceremony.

Uchikake

- Uchikake is a highly formal kimono worn only by a bride or at a stage performance. The Uchikake is often heavily brocaded and is supposed to be worn outside the actual kimono and obi, as a sort of coat. One therefore never ties the obi around the uchikake. It is supposed to trail along the floor, this is also why it is heavily padded along the hem. The uchikake of the bridal costume is either white or very colorful often with red as the base color.

Susohiki / Hikizuri

- The susohiki is mostly worn by geisha or by stage performers of the traditional Japanese dance. It is quite long, compared to regular kimono, because the skirt is supposed to trail along the floor. Susohiki literally means "trail the skirt". Where a normal kimono for women is normally 1.5–1.6 m (4.7–5.2 ft) long, a susohiki can be up to 2 m (6.3 ft) long. This is also why geisha and maiko lift their kimono skirt when walking outside, also to show their beautiful underkimono or "nagajuban" (see below).

Men's kimonos

In contrast to women's kimono, men's kimono outfits are far simpler, typically consisting of five pieces, not including footwear.

Men's kimono sleeves are attached to the body of the kimono with no more than a few inches unattached at the bottom, unlike the women's style of very deep sleeves mostly unattached from the body of the kimono. Men's sleeves are less deep than women's kimono sleeves to accommodate the obi around the waist beneath them, whereas on a woman's kimono, the long, unattached bottom of the sleeve can hang over the obi without getting in the way.

In the modern era, the principal distinctions between men's kimono are in the fabric. The typical men's kimono is a subdued, dark color; black, dark blues, greens, and browns are common. Fabrics are usually matte. Some have a subtle pattern, and textured fabrics are common in more casual kimono. More casual kimono may be made in slightly brighter colors, such as lighter purples, greens and blues. Sumo wrestlers have occasionally been known to wear quite bright colors such as fuchsia.

The most formal style of kimono is plain black silk with five kamon on the chest, shoulders and back. Slightly less formal is the three-kamon kimono. These are usually paired with white undergarments and accessories.

- Date eri or kasane eri

- is a long retangular piece made to resemble a folded kimono collar. It is a decorative accessory used in women's formal kimono styles between the collars of the nagajuban and the kimono to emulate the appearance of wearing an extra layer of kimono beneath.

Datejime or datemaki

- (伊達締め) is a wide undersash used to tie the nagajuban and the outer kimono and hold them in place.

- Eri-sugata or kantan eri or date eri

- (衿姿) is a detatched collar that can be worn instead of a nagajuban in summer, when it can be too hot to comfortably wear a nagajuban. It replaces the nagajuban collar in supporting the kimono's collar.

- Fundoshi

- (褌) is the traditional Japanese undergarment (loin cloth) for adult males, made from a length of cotton.

- Geta

- (下駄) are wooden sandals worn by men and women with yukata. One unique style is worn solely bygeisha.

- Hakama

- (袴) is a divided (umanoribakama) or undivided skirt (andonbakama) which resembles a wide pair of trousers, traditionally worn by men but contemporarily also by women in less formal situations. It is also worn in certain martial arts such as aikido. A hakama typically is pleated and fastened by ribbons, tied around the waist over the obi. Men's hakama also have a koshi ita, which is a stiff or padded part in the lower back of the wearer. Hakama are worn in several budo arts such as aikido, kendo, iaidō andnaginata. Hakama are often worn by women at college graduation ceremonies, and by Miko on shinto shrines. Depending on the pattern and material, hakama can range from very formal to visiting wear.

- Hanten

- (袢纏) is the worker's version of the more formal haori. Often padded for warmth, as opposed to the somewhat lighter happi.

- Haori

- (羽織) is a hip- or thigh-length kimono-like jacket, which adds formality to an outfit. Haori were originally worn only by men, until it became a fashion for women in the Meiji period. They are now worn by both men and women. Men's haori are typically shorter than women's.

- Haori-himo

- (羽織紐) is a tasseled, woven string fastener for haori. The most formal color is white.

- Happi

- (法被) is a type of haori traditionally worn by shop keepers and is now associated mostly with festivals.

- Hiyoku

- (ひよく) is a type of under-kimono, historically worn by women beneath the kimono. Today they are only worn on formal occasions such as weddings and other important social events. High class kimonos may have extra layers of lining to emulate the appearance of hiyoku worn beneath.

- Juban

- Hadajuban

-

- (肌襦袢) is a thin garment similar to an undershirt. It is worn under the nagajuban.

- Nagajuban

-

- (長襦袢, or simply juban) is a kimono-shaped robe worn by both men and women beneath the main outer garment Since silk kimono are delicate and difficult to clean, thenagajuban helps to keep the outer kimono clean by preventing contact with the wearer's skin. Only the collar edge of the nagajuban shows from beneath the outer kimono.Many nagajuban have removable collars, to allow them to be changed to match the outer garment, and to be easily washed without washing the entire garment. While the most formal type of nagajuban are white, they are often as beautifully ornate and patterned as the outer kimono. Since men's kimono are usually fairly subdued in pattern and color, the nagajuban allows for discreetly wearing very striking designs and colors.

- Kanzashi

- (簪) are hair ornaments worn by women. Many different styles exist, including silk flowers, wooden combs, and jade hairpins.

- Kimono slip

- (着物スリップ, kimono surippu) The susoyoke and hadajuban combined into a one-piece garment.

- Karihimo, koshihimo

- (腰紐) is a narrow sash used to aid in dressing up, often made of silk or wool. They are used to hold virtually anything in place during the process of dressing up, and can be used in many ways depending on what is worn. Some of the karihimos are removed after datejime or obi have been tied, while others remain worn beneath the layers of the dress. The karihimo that is worn around the hips to create the extra fold or ohashori in women's kimono is called koshihimo, literally "hip ribbon".

- Netsuke

- is an ornament worn suspended from the men's obi.

- Obi

- (帯) is the sash worn with kimono.

- Obi-ita or mae-ita

- (帯板) is a thin board, often fabric-covered, that is worn beneath the women's obi in front to keep the obi from getting creased.

- (帯揚げ) is an accessory for women's obi, a sash that is tied around the top edge of the obi and which covers the obimakura "pillow" and may keep the upper part of the obi musubi "knot" in place.

- Obimakura

- (帯枕) is a small pillow used to give volume and shape to the female obi styles.

- Obijime

- (帯締め) is a narrow ribbon or cord worn around women's obi. It is necessary to hold the popular taiko musubi in place, and doubles as a decorative element.

- Samue

- (作務衣) are the everyday clothes for a male Zen Buddhist monk, and the favored garment for shakuhachi players.

- Susoyoke

- (裾除け) is a thin half-slip-like piece of underwear worn by women under the nagajuban.

- Tabi

- (足袋) are ankle-high, divided-toe socks usually worn with zōri or geta. There also exist sturdier, boot-like jikatabi, which are used for example to fieldwork.

- Waraji

- (草鞋) are straw rope sandals which are mostly worn by monks.

- Yukata

- (浴衣) is an unlined kimono-like garment for summer use, usually made of cotton, linen, or hemp. Yukata are strictly informal, most often worn to outdoor festivals, by men and women of all ages. They are also worn at onsen (hot spring) resorts, where they are often provided for the guests in the resort's own pattern.

- Zōri

- (草履) are traditional sandals worn by both men and women, similar in design to flip-flops. Their formality ranges from strictly informal to fully formal. They are made of many materials, including cloth, leather, vinyl and woven grass, and can be highly decorated or very simple.

Layering

In modern-day Japan the meanings of the layering of kimono and hiyoku are usually forgotten. Only maiko and geisha now use this layering technique for dances and subtle erotic suggestion, usually emphasising the back of the neck. Modern Japanese brides may also wear a traditional Shinto bridal kimono which is worn with a hiyoku.

Traditionally kimonos were worn with hiyoku or floating linings. Hiyoku can be a second kimono worn beneath the first and give the traditional layered look to the kimono. Often in modern kimonos the hiyoku is simply the name for the double sided lower-half of the kimono which may be exposed to other eyes depending on how the kimono is worn.

Old-fashioned kimono styles meant that hiyoku were entire under-kimono, however modern day layers are usually only partial, to give the impression of layering.

Care of kimonos

In the past, a kimono would often be entirely taken apart for washing, and then re-sewn for wearing. This traditional washing method is calledarai hari. Because the stitches must be taken out for washing, traditional kimonos need to be hand sewn. Arai hari is very expensive and difficult and is one of the causes of the declining popularity of kimono. Modern fabrics and cleaning methods have been developed that eliminate this need, although the traditional washing of kimono is still practiced, especially for high-end garments.

New, custom-made kimonos are generally delivered to a customer with long, loose basting stitches placed around the outside edges. These stitches are called shitsuke ito. They are sometimes replaced for storage. They help to prevent bunching, folding and wrinkling, and keep the kimono's layers in alignment.

Like many other traditional Japanese garments, there are specific ways to fold kimonos. These methods help to preserve the garment and to keep it from creasing when stored. Kimonos are often stored wrapped in paper called tatōshi.

Kimonos need to be aired out at least seasonally and before and after each time they are worn. Many people prefer to have their kimono dry cleaned. Although this can be extremely expensive, it is generally less expensive than arai hari but may be impossible for certain fabrics or dyes.

Cuisine

Through a long culinary past, the Japanese have developed sophisticated and refined cuisine. In recent years, Japanese food has become fashionable and popular in the U.S., Europe and many other areas. Dishes such as sushi, tempura, and teriyaki are some of the foods that are commonly known. According to Japan's Institute of Cetacean Research "Whaling and whale cuisine are part of Japanese culture", and Japan is the world's largest consumer of whale meat. The healthy Japanese diet is often believed to be related to the longevity of Japanese people.

Sports

In the long feudal period governed by the samurai class, some methods that were used to train warriors were developed into well-orderedmartial arts, in modern times referred to collectively as koryū. Examples include kenjutsu, kyūdō, sōjutsu, jujutsu and sumo, all of which were established in the Edo period. After the rapid social change in the Meiji Restoration, some martial arts changed to modern sports, gendai budō.Judo was developed by Kano Jigoro, who studied some sects of jujutsu. These sports are still widely practiced in present day Japan and other countries.

Baseball, football, and other popular western Sports were imported to Japan in the Meiji period. These sports are commonly practiced in schools along with traditional martial arts.

Baseball is the most popular sport in Japan. Football is becoming more popular after J league (Japan professional soccer league) was established in 1991.In addition, There are many semi-professional organizations which are sponsored by private companies. For example ,volleyball, basketball, rugby union,table tennis, and so on. The motorsport of drifting was also invented in Japan.

Popular culture

Japanese popular culture not only reflects the attitudes and concerns of the present but also provides a link to the past. Popular films,television programs, manga, music, and videogames all developed from older artistic and literary traditions, and many of their themes and styles of presentation can be traced to traditional art forms. Contemporary forms of popular culture, much like the traditional forms, provide not only entertainment but also an escape for the contemporary Japanese from the problems of an industrial world. When asked how they spent their leisure time, 80 percent of a sample of men and women surveyed by the government in 1986 said they averaged about two and a half hours per weekday watching television, listening to the radio, and reading newspapers or magazines. Some 16 percent spent an average of two and a quarter hours a day engaged in hobbies or amusements. Others spent leisure time participating in sports, socializing, and personal study. Teenagers and retired people reported more time spent on all of these activities than did other groups.

Many anime and manga are very popular around the world and continue to become popular, as well as Japanese video games, music, fashion, and game shows; this has made Japan an "entertainment superpower" along with the United States and United Kingdom.

In the late 1980s, the family was the focus of leisure activities, such as excursions to parks or shopping districts. Although Japan is often thought of as a hard-working society with little time for leisure, the Japanese seek entertainment wherever they can. It is common to see Japanese commuters riding the train to work, enjoying their favorite manga, or listening through earphones to the latest in popular music on portable music players.

A wide variety of types of popular entertainment are available. There is a large selection of music, films, and the products of a huge comic book industry, among other forms of entertainment, from which to choose. Game centers, bowling alleys, and karaoke are popular hangout places for teens while older people may play shogi or go in specialized parlors.

Together, the publishing, film/video, music/audio, and game industries in Japan make up the growing Japanese content industry, which, in 2006, was estimated to be worth close to 26 trillion Yen (USD$ 400 billion.).

National character

The Japanese "national character" has been written about under the term Nihonjinron, literally meaning "theories/discussions about the Japanese people" and referring to texts on matters that are normally the concerns of sociology, psychology, history,linguistics, and philosophy, but emphasizing the authors' assumptions or perceptions of Japanese exceptionalism; these are predominantly written in Japan by Japanese people, though noted examples have also been written by foreign residents, journalists and even scholars.

In terms of comparative cultural characteristics at the world level, the cultural map of the world according to the World Values Survey describes Japan as highest in the world in "Rational-Secular Values", and average-high in "Self-Expression Values".

0 Comments:

Post a Comment